Coppicing is a traditional form of woodland management that has shaped many of the remaining semi-natural woodlands in the UK.

Periodic cutting actually prolongs the life of the tree as well as creating a rich mosaic of habitats, attracting a wide range of flora and fauna. Woods that have not been coppiced tend to be of the same age and structure, supporting fewer species.

The market for coppice products is growing – for high quality timber standards and also for traditional goods such as wattle hurdles and turned products. Derelict woodlands have little timber value – so the future is optimistic.

What is a coppice?

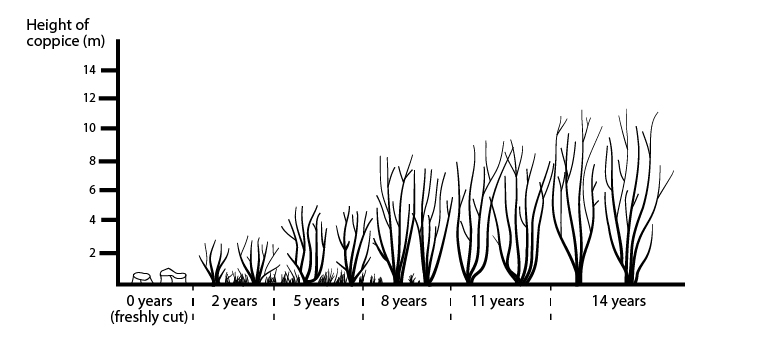

A coppiced wood is cut periodically, with the trees allowed to regrow from the cut stumps, called stools. This produces numerous shoots or poles rather than one main stem. Regrowth can be very fast, often as much as two metres in a year. These stools can be coppiced indefinitely to provide a self-renewing source of wood. Often the oldest trees in our woods are grown from coppice stools and pollarded trees (those cut above cattle and deer grazing height) – some are more than a 1,000 years old.

Traditionally woods were divided into compartments, called a cant, coupe, panel, fell, sale, burrow or hagg depending on which part of the country the wood was in. These were cut in rotation. Each compartment would contain an ‘underwood’ which was coppiced, and scattered ‘standards’ or timber trees. A coppice without standards was called a simple coppice.

The underwood storey can be dominated by one, or contain a mix of species such as hazel, alder, ash, crab apple, field maple, oak, goat willow, small-leaved lime, sweet chestnut and wych elm, beech and hornbeam. The age that coppice panels are cut depends on the species and what the wood will be used for.

Woodland wildlife

Coppicing leaves an irregular patchwork of panels of different ages – ideal for wildlife, particularly those species requiring an open woodland habitat.

Plants

When a new coppice panel is cut more light is let into the wood, four times more in spring and up to 20 times more in midsummer. This produces a sequence of changes in the plant life. First it stimulates a surge of growth from dormant seed and plants. In the second or third year, spring flowers, such as bluebells, oxlips, violets, primroses, wood anemones, ground ivy, yellow archangel and water avens, will carpet the ground.

More vigorous, light demanding species, such as grasses and brambles do not get a chance to dominate as the coppice canopy closes between five to eight years after cutting. This rapidly shades out most of the foliage underneath. But a few plants, such as dog’s mercury and herb paris prefer the shady conditions of older coppice.

Butterflies

Woodlands support more species of butterfly than any other habitat in the UK. Most butterflies have just one, or a small number of plants which their larvae will feed on and a poor ability to reach new, more suitable habitats. Usually these plants occur in open sunny areas created by coppicing or along woodland rides. Species such as the Duke of Burgundy fritillary whose larvae thrives on primrose, and the heath fritillary which needs cow wheat, wood sage or foxglove, have declined because of loss of habitat through neglected woodlands.

Insects

Insects like the warm microclimate and diverse vegetation of young coppice. Large numbers of ground species such as wolf spiders and ground beetles establish a year after cutting followed by numerous and diverse species in years two to five.

Mammals

Small mammals, like birds, are strongly influenced by the coppicing cycle. Mice, shrews and voles are often the first to appear in recently cut coppice. By the third year the small mammal population will probably be at a peak before decreasing gradually until the cycle is repeated.

Coppiced woodland in south and west England is one of the most important habitats of the common dormouse which needs a high diversity of tree species to provide food throughout the year. Dormice spend most of their lives in branches and foliage and require a continuous canopy of coppice and standards, but do not thrive in very old coppice.

The succulent young shoots from the coppice stools attract browsing deer. Large deer populations of today may mean that stools need covering with brash, or brash fences built around newly cut coupes, to protect the regrowth.

Birds

In general, birds will take advantage of the flourishing insect life. But different species prefer different parts of the cycle. In very open coppice, during the first three or four months of growth, tree pipits can be the first to colonise sweet chestnuts, followed by yellowhammers, linnets and whitethroats.

By the third or fourth year, when low vegetation is becoming dense, there will be summer visitors such as the garden warbler, willow warbler, nightingale, blackcap and chiffchaff. They remain until about the 10th year and rapidly decrease afterwards.

Old coppice species include the robin, blackbird, chaffinch, great tit and blue tit. If the coppice contains large mature standard trees, woodpeckers, nuthatches and treecreepers will often be present.

Traditional crafts

The practice of coppicing dates back to Neolithic times. Evidence suggests the Romans coppiced large areas of the Wealdon woodlands to fuel their iron works. Later, records in the Domesday Book of 1086 show that coppicing was widespread in lowland England. By the Middle Ages short-rotation (every six years) coppice was the most common form of woodland management.

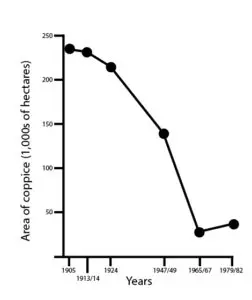

But the craft of coppicing has been in decline since the demand for coppice products began to falter last century. By 1965, the area of coppiced woodland was as low as 30,000 hectares. The recent modest revival is mainly due to conservation organisations’ efforts to preserve the historical heritage, rich wildlife habitat and rural crafts associated with coppicing. Now an increasing number of commercial, statutory and voluntary bodies, including TCV, are exploring the economics of coppice products.

The market for coppice

The underwood was a valuable product so little was wasted. Building and fencing materials and firewood were the most common uses, with the twigs used as faggots, but also the supple young shoots were used for hedging.

Whole or split sallow or hazel rods were interwoven to form the ‘wattle’ used to fill in the panels of timber-framed buildings.

Coppice products – past and present

- Birch: brooms and brushes, turned products, horse jumps and cotton reels.

- Hazel: hurdles, thatching spars, runners and pegs, rabbit and deer snares, fish traps, pea sticks, shepherd’s crooks, wattle fencing and heathering.

- Sweet chestnut: hop poles, cleft fences, tent pegs.

- Small-leaved lime: carving wood, hat blocks, spoons, ditching shovels, fine joinery.

- Hornbeam: mallets, piano keys, skittles and balls, golfclub heads.

- Ash: tool handles, yacht masts, barrel hoops, crutches, cart shafts and wheel felloes and timber.

- Oak: bark for tanning, fencing, ship building, roofing shingles, ladder rungs, barrels and cudgels.

- Willow: basket making, coarse screen work, living fences, clog soles, water mill paddles.